Antibacterial Targets - Evidence for exclusion of targets for which host orthologues exist

One of the classic mantras for the genomics-based discovery of novel anti-bacterials is to ignore targets for which orthologues exist in the host (human) genome, but my hunch was that the majority of antibacterial mechanisms have clear host orthologues (they do, as you'll see below). I haven't come across any really simple papers supporting this dogma in the past, so decided to have a quick look this morning. I am the unwilling host for an oral bacterial infection myself at the moment, but I must stress that the throat above is not mine, but an anonymous one from Teh Interweb!

So, using a book I've just picked up at the ACS in Indy, I went through and did some quick analysis - the prose in the book is great, informal, and very very readable - buy it!

%T Antibacterial Agents: Chemistry, Mode of Action, Mechanisms of Resistance and Clinical Applications %A R.J. Anderson %A P.W. Groundwater %A A. Todd %A A.J. Worsley %I Wiley %D 2012 %O ISBN 978-0-470-97245-8

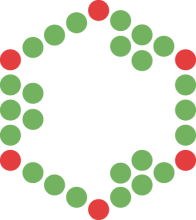

I went through, and at a drug class level, assigned the distinct mechanisms into three target classes.

- Orthologue of antibacterial target is present in humans.

- Orthologue of antibacterial target is absent in humans.

- Antibacterial acts through a non gene-derived target mechanism.

So, no real great evidence to focus on bacteria specific genes - in fact it's 2:1 in favour of targets for which orthologues exist in the host. The key would seem to be more exploiting physicochemical differences between bacterial and human cells (e.g. acidity), or exploit differences in the binding sites. I guess the dogma arose for a couple of reasons - firstly everyone knowns about penicillins, and secondly, it is an easy filter to apply bioinformatically, and finally it just seems like a perfectly sensible thing to do with respect to elimination of mechanism-based toxicity - and so is often done.

On this latter point, that of mechanism-based toxicity, this can be really important, but remember, a drug dosed to a human is not magically attracted only to relatives of the bacterial target, it will sample and equilibrate across all accessible binding sites of all proteins, and drugs will have side-effects and toxicity related to 1) binding to orthologues, 2) binding to paralogues, and 3) binding to anything else. A nice example of this is the paper from Science earlier this year on the side effects of sulphonamide antibacterials via inhibition of host sepiapterin reductase.

To be clear what I did here. Firstly - I used the chapters in the Antibacterial Agents book to define a class, so the graph can be plotted in many other ways - however, I was interested in distinct mechanisms. Secondly, several antibacterials don't target proteins, but various parts of the ribosome - these are gene derived, so count above as gene products, but they are not proteins (well they are riboproteins). Even if you strip these RNA targets out though (there are 5) the numbers are still not compelling for the need to avoid host target orthologues - the ratio would be 3:4 instead of 8:4.

What are the implications of removing this bacterial specific filter? Well that is more than a quick job on a Sunday morning and two cups of Lapsong Suchong - but my feeling is it might be quite significant.

jpo